Understanding Huntington Disease: A Genetic Impact on Brain Health

Table of Contents

Understanding Huntington Disease: A Genetic Impact on Brain Health

Living with the uncertainty of a serious health condition or caring for someone facing significant challenges can feel isolating. I know you may be asking, what is Huntington disease, and how does it affect people? Huntington disease (HD) represents an inherited brain disorder where nerve cells experience gradual decline. This breakdown affects movement control, thinking abilities, and emotional regulation, creating complex hurdles for individuals and their families. At its core, a tiny alteration within a single gene, the HTT gene, on chromosome 4, causes this condition. This alteration involves an excessive repetition of a particular “CAG” DNA sequence. More repeats typically correlate with an earlier onset of symptoms and a more aggressive disease progression. This genetic reality means a child born to a parent with HD faces a 50% chance of inheriting the disease. The condition does not skip generations. Onset often appears between ages 30 and 50, yet sometimes earlier, called Juvenile HD, or even later in some instances. HD follows a slow course, typically progressing over 10 to 25 years. This article explores the nature of Huntington disease, examining its historical context, symptom presentation, diagnostic considerations, and the accelerating scientific efforts offering hope for tomorrow.

Defining Huntington Disease: A Genetic Blueprint of Brain Cell Deterioration

Imagine a scenario where the precise coordination of a complex system gradually falters. This parallels the impact of Huntington disease on the brain. This genetic disorder causes particular nerve cells, especially in regions vital for movement and thought, to waste away over time. The consequence manifests as a progressive decline in various functions, creating profound changes in an individual’s life.

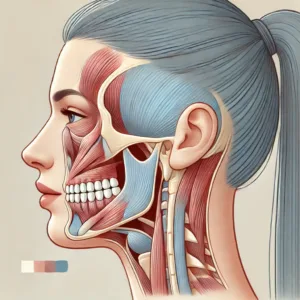

The root cause of Huntington disease lies in a genetic mutation. Specifically, a defect appears in the huntingtin (HTT) gene located on chromosome 4. This gene carries instructions for producing the huntingtin protein, a component crucial for normal brain cell function. In people with Huntington disease, an abnormal expansion occurs in a segment of this gene—a sequence of DNA building blocks known as cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG). While most individuals possess fewer than 36 CAG repeats, those with Huntington disease display 36 or more. This overextended repeat sequence leads to the formation of an altered, toxic version of the huntingtin protein, which disrupts cellular processes and eventually kills brain cells.

The inheritance pattern of Huntington disease operates under an autosomal dominant model. This means that inheriting just one copy of the mutated HTT gene from an affected parent is sufficient for a person to develop the disease. Each child of a parent with the altered gene has a 50% chance of inheriting it. If a child does not inherit the mutation, they will not develop the disease nor carry the risk of passing it to their own children. Though rare, instances exist where Huntington disease arises without a known family history, designated as sporadic HD. Understanding this genetic foundation is fundamental to grasping the condition’s progression and its profound implications for families.

I recall a conversation with a family where HD runs. The weight of genetic destiny, the mathematics of chance, they were almost unbearable. “Every child born,” a mother once told me, her voice thin with a profound melancholy, “is a roll of the dice. We simply live with this lingering apprehension.” This sentiment encapsulates the unique burden families contend with.

Huntington Disease Through Time: From Mystery to Molecular Discovery

The presence of unusual, involuntary movements has puzzled observers for centuries. Early mentions of bizarre, jerky body movements appear in medieval accounts, sometimes attributed to phenomena like the “dancing plague.” These historical references, though lacking modern scientific clarity, offer a glimpse into the long recognition of such unique motor patterns.

The formal identification of Huntington disease arrived in 1872 through the work of George Huntington. A young American physician, only 22 years old, Huntington authored a seminal paper titled “On Chorea.” Drawing upon observations spanning multiple generations within families in East Hampton, Long Island—a medical heritage passed down through his father and grandfather—he composed a remarkably precise description of this hereditary, dance-like disorder. Huntington illuminated a distinct grouping of symptoms: chorea that starts in adulthood, mental changes, and a clear pattern of inheritance. This detailed account, groundbreaking for its time, established the condition as Huntington disease.

Decades passed with limited progress on the underlying reasons for the disease. However, the 1960s sparked a turning point. The advocacy work of Marjorie Guthrie, wife of the renowned folk musician Woody Guthrie (who died from Huntington disease), mobilized affected families. Her dedication helped establish a foundation that paved the way for the Huntington’s Disease Society of America (HDSA). This effort generated public awareness and invigorated scientific investigation.

The most significant advancement occurred in 1993. An international collaborative effort, propelled by researchers including Nancy Wexler, whose family was also affected by HD, successfully located the specific gene responsible for Huntington disease. This gene, found on chromosome 4, harbors an unusually expanded CAG repeat sequence. This monumental finding transformed diagnosis, enabling genetic testing to confirm the disease with a blood sample and providing predictive testing for individuals at risk. The identification of this gene represented a pivotal achievement, making Huntington disease one of the first genetic conditions for which the specific gene was found. We now appreciate how complex conditions can arise from seemingly small genetic deviations, pushing the frontiers of medicine.

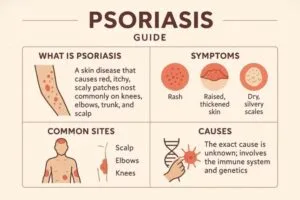

The Manifestation of Symptoms: What Huntington Disease Looks Like

Huntington disease presents a complex and varied set of symptoms, which often progress slowly and can appear differently across individuals. The condition typically manifests as a “triad” of motor, cognitive, and psychiatric challenges, each adding layers to the lived experience of someone with the disease.

Physical Movement Changes:

The most recognizable physical symptom of Huntington disease involves involuntary jerks and twitches, medically termed chorea. This gives the condition its older name, “Huntington chorea.” These movements often start subtly in the hands, fingers, or face, before extending to the arms, legs, and torso, resembling an unruly dance. Imagine trying to hold a glass of water, but your arm decides it has other plans; such is the impact of chorea. Beyond chorea, individuals might experience:

- Balance difficulties: An unsteady gait, leading to clumsiness and frequent falls.

- Speech difficulties: Slurred words, making communication difficult.

- Swallowing problems: Dysphagia, creating challenges with eating and drinking.

- Muscle stiffness: In later stages, rigidity or dystonia (sustained muscle contractions) can replace the jerky movements, leading to slower, more restricted motion.

For children and young adults with Juvenile Huntington Disease (JHD), symptoms sometimes appear more like Parkinson disease, showing rigidity and slow movements, rather than prominent chorea. Seizures can also occur in JHD, adding another layer of complexity.

Cognitive Changes:

The mind also experiences significant alterations. Individuals with Huntington disease often report trouble with:

- Planning and organization: Difficulty arranging tasks or anticipating consequences.

- Memory and focus: Challenges recalling recent events or sustaining attention.

- Decision-making: Impaired judgment, leading to difficulties in daily choices.

- Learning new information: A reduced capacity to absorb and process novel concepts.

These cognitive impairments can gradually worsen, eventually progressing to a form of dementia.

Psychiatric and Emotional Shifts:

The emotional landscape can become unpredictable. Mood swings, irritability, depression, and anxiety are common. It is not simply a reaction to the diagnosis; often, these emotional changes stem from the actual changes happening within the brain.

- Apathy: A significant loss of interest or motivation.

- Impulsivity: Acting without considering consequences.

- Personality changes: A shift in overall disposition.

- Aggression: Occasional outbursts of anger.

- Obsessive-compulsive behaviors: Repetitive thoughts or actions.

A person once told me, “It was like watching a switch flip. The person I knew was still there, but overshadowed by these abrupt, inexplicable emotional storms.” This speaks to the profound impact of these psychiatric symptoms, which can be as distressing as the physical ones. It takes a comprehensive approach to support individuals and their families as they learn to manage these varied and progressive symptoms.

Genetic Testing for Huntington Disease: Weighing the Personal Impact

The question of genetic testing for Huntington disease often represents a deeply personal and complex decision. Genetic testing provides a definitive answer by counting the specific CAG repeats in the HTT gene. A number of 36 or more repeats confirms the presence of the mutation for HD. This objective scientific fact, however, carries immense subjective weight.

The Dilemma of Knowing:

For individuals at risk, knowledge of a genetic destiny without a cure presents significant emotional and psychological challenges. The thought of confirming a future with a progressive, debilitating illness can bring profound distress, including:

- Depression and anxiety: The burden of knowing can trigger severe emotional responses.

- Increased risk for suicide: Studies suggest a higher risk for individuals receiving a positive test result, underscoring the need for careful counseling.

- Survivor’s guilt: Those who test negative sometimes experience guilt towards family members who receive a positive diagnosis.

A medical colleague shared a story about a young man who had the test. He explained, “The result came back negative. He felt relief, yes, but then a different burden settled in—the silent question, ‘Why me, and not my brother?’ It fractured his peace in an unexpected way.” This illustrates the nuanced psychological terrain involved.

Family and Societal Reflections:

The results of genetic testing for Huntington disease resonate through generations. Such information can initiate difficult conversations and create strain within families.

- Disclosure challenges: Deciding who to tell, and when, especially regarding children, becomes a sensitive family matter.

- Reproductive choices: For those of childbearing age, genetic testing introduces difficult choices about having biological children, with options like preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) raising ethical questions about “designer babies” or selective termination.

- Stigma: A lack of broad public awareness about Huntington disease can lead to misunderstanding, social isolation, and discrimination. People with the condition often encounter prejudice in employment, housing, and even in healthcare settings.

Consider the historical shadow: in 1910, some proposed compulsory sterilization for individuals with Huntington disease as part of the eugenics movement. This dark chapter highlights the historical societal misunderstanding and fear surrounding genetic conditions. While society has evolved significantly, the stigma can linger. Adequate genetic counseling, psychological support, and community education remain vital resources for individuals and families facing these profound personal and societal considerations.

Advancements for Huntington Disease: Current Care and Future Promise

While a cure for Huntington disease remains elusive, treatment today focuses on managing symptoms and improving comfort, with a rapidly accelerating research landscape pointing to significant future promise. Our collective efforts seek to make life better for those affected.

Current Symptom Management:

Treatment plans for Huntington disease often require a multidisciplinary approach, involving a team of specialists to address the varied symptoms.

- Medication for Movement: Drugs like tetrabenazine, deutetrabenazine, and valbenazine help control chorea by affecting neurotransmitter levels in the brain. Antipsychotics can also assist with both movement and behavioral challenges.

- Medication for Psychiatric Symptoms: Antidepressants (such as fluoxetine or sertraline), antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers manage symptoms like depression, anxiety, irritability, and mood swings.

- Supportive Therapies:

- Physical therapy: Helps with movement, balance, and gait.

- Occupational therapy: Provides strategies for daily activities and home adaptations.

- Speech therapy: Assists with communication and swallowing difficulties.

- Genetic counselors and social workers: Offer essential support and guidance for families.

“My speech therapist, she is a lifesaver,” one person confided. “Before, eating was terrifying. Now, I have strategies, methods to make it less risky, more enjoyable. It is not perfect, but it is progress.” This small improvement speaks volumes to the immediate impact of dedicated care.

Pioneering Research and Emerging Therapies:

The future for Huntington disease brings tangible hope through cutting-edge research. Scientists target the disease at its genetic foundation.

- Gene Silencing: The goal involves “turning off” or significantly reducing the production of the toxic mutant huntingtin protein.

- Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs): These synthetic molecules bind to messenger RNA (mRNA) from the HTT gene, signaling the cell to destroy it before the harmful protein is made. Tominersen and WVE-003 represent ASO therapies undergoing trials.

- RNA Interference (RNAi): Similar to ASOs, RNAi therapies use small RNA molecules to interfere with the production of the mutant protein.

- Gene Editing Technologies: Tools like CRISPR/Cas9 offer the potential to edit or inactivate the mutant HTT gene directly at the DNA level, aiming for a permanent correction.

- Small Molecule Oral Drugs: Companies like Arvinas and ReviR Therapeutics are developing oral medications that reduce the bad protein or slow problematic DNA changes. Votoplam and pridopidine are other small molecules in investigation.

- Gene Therapies: These “one-time” treatments deliver genetic material directly into brain cells via a harmless virus. uniQure’s AMT-130, injected into deep brain areas, showed promising results in a small study, slowing disease progression by an average of 75% over 30 months in high-dose recipients. This is a significant finding.

- Other Avenues: Scientists also explore stem cell therapies to replace damaged brain cells, and drugs that target neuroinflammation, an immune response observed early in the disease progression. Recent research indicates the CAG repeat in the HTT gene continues to expand within somatic cells over decades, pushing a toxic threshold that initiates cell death. New therapies might target this specific expansion.

These advancements represent a monumental shift. The field moves beyond just managing symptoms to actively modifying the disease course.

Moving Forward with Huntington Disease: A Path of Progress and Advocacy

The journey with Huntington disease presents profound individual and family challenges, yet the scientific horizon brightens with relentless research and dedicated advocacy. Our collective momentum drives us closer to impactful solutions, offering a clearer, more hopeful future for many.

The relentless pace of research in genetic and neurological sciences offers unprecedented possibilities for Huntington disease. We are on the cusp of truly altering the course of this condition. Innovations in gene therapy, such as uniQure’s AMT-130, provide compelling evidence that disease modification, previously a distant aspiration, could become a reality. Imagine therapies that not only alleviate symptoms but actively slow or even halt the insidious brain cell deterioration. This represents a fundamental shift in medical strategy.

Patient advocacy and participation are absolutely vital to accelerate these breakthroughs. Clinical trials, for instance, depend entirely on the willingness of individuals to engage. Programs like HD Trialfinder connect patients, caregivers, and healthy volunteers with ongoing studies, ensuring diverse participation critical for robust data and swift progress. Each person’s involvement contributes an irreplaceable piece to the puzzle.

Here is what remains crucial for families facing Huntington disease:

- Stay informed: Engage with reputable organizations like the Huntington’s Disease Society of America (HDSA) to access the latest information.

- Seek multidisciplinary care: A coordinated team of specialists can provide holistic support for symptoms.

- Consider genetic counseling: For those at risk, counseling offers essential guidance through complex decisions.

- Explore clinical trial participation: Contribution to research is a powerful form of action.

Though a definitive cure is not yet universally available, the blend of expert symptomatic management and groundbreaking disease-modifying therapies means families facing Huntington disease can look towards a brighter future. We continue the work, committed to turning hope into concrete health advancements. Huntington disease will face our persistent collective effort.

Common Questions About Huntington Disease

What is Huntington disease?

Huntington disease is an inherited brain disorder causing nerve cells to gradually break down, leading to difficulties with movement, thinking, and emotional regulation. It stems from a specific genetic mutation.

How is Huntington disease inherited?

It follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. This means if one parent has the altered gene, each child has a 50% chance of inheriting the gene and developing Huntington disease.

What are the main symptoms of Huntington disease?

Symptoms typically involve a triad of progressive issues: involuntary movements (chorea), cognitive difficulties (problems with memory, planning), and psychiatric changes (mood swings, depression, anxiety).

When do Huntington disease symptoms usually start?

Onset commonly occurs between ages 30 and 50, but can appear earlier (Juvenile HD) or later in some individuals.

Can genetic testing diagnose Huntington disease?

Yes, genetic testing can definitively confirm Huntington disease by counting the number of CAG repeats in the HTT gene. Genetic counseling is an important part of this process.

Are there treatments for Huntington disease?

Currently, there is no cure to halt the disease progression, but medications and therapies exist to manage symptoms, improving comfort and quality of life for people with Huntington disease. Research into disease-modifying treatments is rapidly advancing.

What new treatments for Huntington disease are on the horizon?

Emerging therapies focus on gene silencing (like ASOs), gene editing (CRISPR), oral small molecules, and gene therapies (like AMT-130), aiming to address the underlying genetic cause and slow disease progression.

Post Comment